Text and powerpoint by Javier Fatás

(a teacher of the Department of Language and Literature)

«La última balada

de Oscar Wilde» aparenta ser una crónica de periódico, entrecruzada con un

cuento, algo habitual en la prosa modernista muy ligada a la información periodística

y al relato corto. El texto

empieza escrito como una crónica que relata hechos reales del

escritor irlandés en París, a continuación una charla que Manuel Machado y Wilde mantienen por paseos y cafés

de París y en la que Wilde narra un cuento con un motivo folclórico tradicional

(el anillo mágico), como un acto más del diálogo que ambos. El café se

convierte a finales del XIX para los escritores bohemios en un lugar social y

la charla de café se presenta varias veces en el relato.

Hay en la balada de Machado un aspecto

recordatorio de la figura y obra de Wilde, que correspondería con la escritura

en forma de crónica, a veces con cierto resabio de intimidad confesional. La

continua presencia de la ciudad de París, bien como lugar de asiento de Wilde

tras su incidente en Inglaterra, bien en su aspecto más urbano, con un paseo

recorrido por Wilde y Machado, articulará la crónica y el cuento. La ciudad de

Paris servirá para explorar posibilidades sensoriales, cromáticas, plásticas

que relacionarán la escritura de Machado con la prosa modernista.

El relato comienza con el apartado de crónica

recordando la relación entre París y Oscar Wilde. En París, que se declaró

ferviente apasionado de Wilde, se entusiasmaron con Salomé, con su Retrato de

Dorian Grey, de la que dice que los parisinos lo tuvieron como breviario. Repasa cómo lo postergó la sociedad inglesa

tras el asunto de su enamoramiento con Alfred Douglas, y cómo la sociedad

francesa también lo orilló cuando ya vivía "canoso y algo encorvado"

«París leyó con pena y encanto su Balada

de la Cárcel, la Ballade

of Reading Geole, y después, poco a poco, dejó de hablar de él, como él de

escribir»

Incluso su relación con el poeta Jean

Lorrain, "elegantísimo golfo de París, con su alma femenina de cronista

chismoso y entrometido, le disgustó francamente".

Una vez presentada la figura de Wilde en

París, Manuel Machado relata cómo se encontró con Wilde, en un bar, el Calisaya

"una taberna internacional del boulevard de los italianos". Entramos

en un tema muy querido por los modernistas las charlas de café, que se

mantuvieron en la literatura del XX como un marco de relación entre escritores.

Los tertulianos del café serán un poeta

modernista francés de origen griego, Jean Moréas, Oscar Wilde y el propio

Machado de quien se dice "nacido en la Macarena". Machado describe el

cafe y las gentes que pasan por el boulevard "desde la gran cocotte que va

a trabajar al Bois de Boulogne" hasta la "humilde obrerita".

A continuación deja hablar a Wilde para

narrar un relato basado en un anillo mágico: "la sortija de la

desgracia".

El relato tiene componentes propios de Wilde,

el misterio, el culto a los objetos, la visión de la belleza sensual por encima

de la naturalista de Zola, la ambientación del Sena y barrios de París como

Montmartre; y también de la cultura de finales de siglo (tertulia de café con

escritores).

La historia de la sortija, reencontrada por

los camareros del hotel, le lleva otra vez a la mala fortuna y a la tristeza.

Finalmente Machado entrecruza los dos géneros

y las dos historias, la del cuento de la sortija que le traerá mala suerte, y

la de la crónica de Machado, que termina con la noticia de la muerte de Oscar

Wilde.

Oscar wilde visto por manuel machado en su última balada de oscar wilde (2) from pilarmham

_________ o O o __________

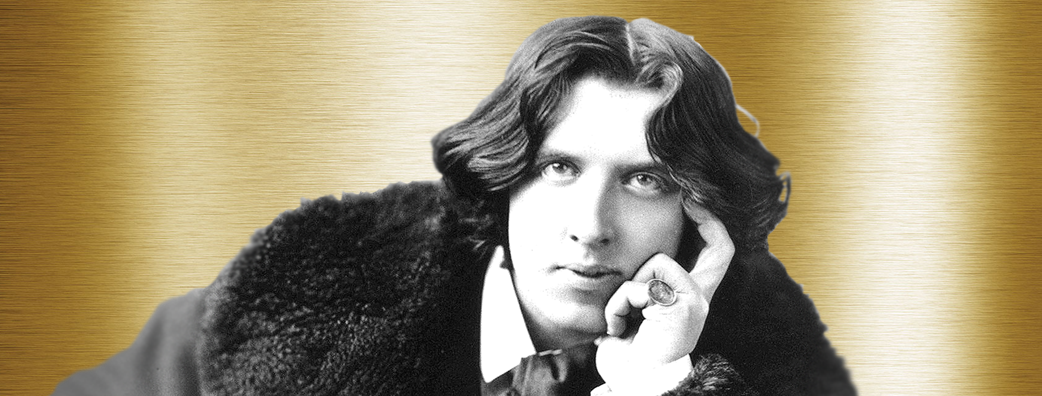

Oscar Wilde by Ana Matamala

(a teacher of the English Department)

Ana and her creation:

_________ o O o __________

Oscar Wilde as seen by José Antonio Marcén

(a teacher of the Art Department)

_________ o O o __________

From an anonymous teacher

_________ o O o __________

Ellmann starts every chapter with a quotation of Wilde’s words and after that provides us with a thorough display of details of his writings, life, relations, joys, and misfortunes. Under this light we confirm what we could glimpse when reading every one of his books, that Wilde was pure excess, just like life, and he could not be stopped by morals, even though these could (and did) crush him. “Though he offered himself as an apostle of pleasure, his created work contains much pain” (p. xiv).

“Essentially Wilde was conducting, in the most civilized way, an anatomy of his society, and a radical reconsideration of its ethics. He knew all the secrets and could expose all the pretense. Along with Blake and Nietzsche, he was proposing that good and evil are not what they seem, that moral tabs cannot cope with the complexity of behavior. His greatness as a writer is partly the result of the enlargement of sympathy which he demanded for society’s victims” (p. xiv). “We inherit his struggle to achieve supreme fictions in art, to associate art with social change, to bring together individual and social impulse, to save what is eccentric and singular from being sanitized and standardized, to replace a morality of severity by one of sympathy” (p. 553).

(ELLMANN, Richard. Oscar Wilde. London: Penguin Books, 1987)

_________ o O o __________

_________ o O o __________

Oscar Wilde by Ana Matamala

(a teacher of the English Department)

Ana and her creation:

_________ o O o __________

Oscar Wilde as seen by José Antonio Marcén

(a teacher of the Art Department)

_________ o O o __________

From an anonymous teacher

This is a summary of an excellent book on Oscar Wilde written by Richard Ellman, an American literary critic who wrote acclaimed biographies of three Irish writers: Oscar Wilde, James Joyce and William Butler Yeats.

We can but highly recommend a magnificent biography of Oscar Wilde by the author of other excellent biographies, such as Joyce’s: Oscar Wilde, by Richard Ellmann. Ellmann offers us his profound knowledge of Wilde with the utmost credibility, unaffected by his obvious devotion towards the writer and the person. The riches and precision of the vocabulary that he employs and the vast array of facts about Wilde’s work and life give the reader a sensation of following Wilde and even being an observer of his contradictions, delights, afflictions, and, what’s more important, of his development as a human being.

Ellmann starts every chapter with a quotation of Wilde’s words and after that provides us with a thorough display of details of his writings, life, relations, joys, and misfortunes. Under this light we confirm what we could glimpse when reading every one of his books, that Wilde was pure excess, just like life, and he could not be stopped by morals, even though these could (and did) crush him. “Though he offered himself as an apostle of pleasure, his created work contains much pain” (p. xiv).

He was the best company, witty and an unequalled conversationalist, always generous with his guests and acquaintances, lovers or even strangers. He didn’t receive the same token when he was accused of immorality and sent to prison. Most of his friends abandoned him and refused to help, and the few years he lived after being in jail he was ruined. He died in exile accompanied only by a couple of friends, Reggie Turner and especially Robert Ross, who never left him. His personality and his intelligence were not fit for the times, which were but rigid and hypocritical, and nothing was more alien to Wilde, whose passion for life was endless and could not possibly be hidden. Life or art, what comes first? Both were irresistible for Wilde, but there can be no doubt when knowing him in such depth as Ellmann does: Life is generosity and splendor, but it comes second, as it can only imitate art, and only the latter can come near perfection and is a mirror to life. Art is the true creator, and only creators can shape life. This explains why Wilde was so careful with every detail, every word he chose, every garment he wore, his hair, his surroundings, his home and its decoration, etc. Everything had to be perfect, a work of art, for life deserves no less. Morality is only a constraint and limits the creator. Only intelligence and taste can prevail. That’s why he never confined himself to one specific faith or group (he played with the idea of becoming a Christian and joined masonry at the same time!). Why not taste them all? He had to be sent to prison by the society that he had exposed to put limits to his passion for life, and that killed him. We can imagine the suffering of such sensibility imprisoned. No blue china, no champagne, no books, no words, no air. A man of his delicacy could not survive the lack of beauty and the fetid air of jail. His purity was suicidal.

“Essentially Wilde was conducting, in the most civilized way, an anatomy of his society, and a radical reconsideration of its ethics. He knew all the secrets and could expose all the pretense. Along with Blake and Nietzsche, he was proposing that good and evil are not what they seem, that moral tabs cannot cope with the complexity of behavior. His greatness as a writer is partly the result of the enlargement of sympathy which he demanded for society’s victims” (p. xiv). “We inherit his struggle to achieve supreme fictions in art, to associate art with social change, to bring together individual and social impulse, to save what is eccentric and singular from being sanitized and standardized, to replace a morality of severity by one of sympathy” (p. 553).

(ELLMANN, Richard. Oscar Wilde. London: Penguin Books, 1987)

_________ o O o __________

No comments:

Post a Comment